“How the hell do you know how ‘successful’ a project is when you’re creating ads for global tire companies?”

I remember wrestling with this question after seeing the meteoric rise of a local interactive agency that’s done work for Google, HBO, FedEx, Gillette, and tire manufacturers like BFGoodrich.

At around the time when I was brooding over this question, I was focused on growing my own small consultancy a few blocks down the street. And while both of our companies employed designers and developers and worked for clients, the similarities ended there.

My company focused on small businesses and startups that had solid business plans in place and needed someone to help them amplify their profits. We’d often come in to rewrite and reimplement legacy internal software that was creating a bottleneck internally. Or we’d help kick off new web and mobile apps with the intent that they’d generate more leads, more sales, and more of whatever financially-motivated thing our client needed us to do.

Grow, on the other hand, made really impressive interactive advertisements. If you remember the age of full-page Flash animations, this was how they got their start. They’d create beautiful and immersive experiences for brands that were a lot of fun to play around with and — presumably — ultimately profitable for their clients.

But I just couldn’t figure it out.

Here I was Socratically questioning my clients and trying my best to gauge the additional profit that our projects would bring to our clients… and down the street, a much more successful, much bigger agency was selling projects that were impossible to quantify the value of.

How many new tires will be sold because people see an ad featuring Olympic gold medal winner Shaun White drifting around a track in a race car? Impossible to tell.

Similarly, do you remember those ads that they’d play before movies that featured animated polar bears drinking Coca-Cola?

Do you think anyone has any idea how many cans of coke sold as a direct result of those ads?

Of course not.

And in the mind of this metrics-obsessed engineer-turned-consultant, that drives me crazy.

And I don’t seem to be the only one.

Every time I give a talk on or teach somebody about value-based pricing, I get asked: How to do you value projects that don’t have an obvious financial ROI?

It’s not always about the money

Money isn’t always a motivator for clients.

For my clients, it usually was. But the people who hired me were often CEOs of 20-something person companies. The money they spent on my team and I could have been invested in any number of different ways: hiring, buying equipment, paying off debt, or affording quite a few fully loaded vacations for the business owner and their family.

But for mega companies like the type that routinely hire agencies like Grow, money wasn’t the motivator.

Rather, the client — e.g. a marketing department — was usually earmarked a fixed budget each fiscal year to spend on projects. The decision maker generally won’t see any effect on their pay as a direct result of more tires sold. They’re so far removed from any department that touches money that they’re totally insulated. And frankly, they probably don’t care how many tires Grow sells for them.

What they do care about, though, is status.

My friend Josh Kaufman, the best-selling author of The Personal MBA, talks about “Status Seeking.” His theory is that people really care about what people think of them, so it’s in the best interest of people to associate themselves with people who will increase their perceived status.

In general, we like to be associated with people and organizations that we think are powerful, important, exclusive, or exhibit other high-status qualities or behaviors. We also like to ensure other people are aware of our status: for proof, examine what people post on their Facebook profiles.

Status Seeking is a fact of human life: it’s not necessarily bad or something to be a avoided. On the contrary: Status Seeking can motivate people to accomplish amazing things. In the words of Alain de Botton, a philosopher and social critic, “If one felt successful, there’d be so little incentive to be successful.”

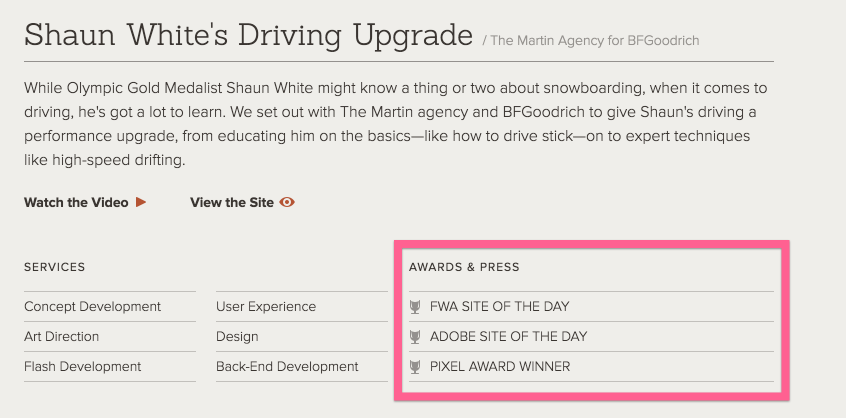

The case study that Grow produced about their engagement with BFGoodrich highlights the increase of status that this project delivered, both for Grow and their client:

This project won the “Flash Website Award” (back when that was a thing), the Adobe Site Of The Day, and the Pixel Award.

And looking at Grow’s agency overview page, you also see that they’ve won a Grand Prix award at Cannes, 11 Cannes Lions, 4 Webby Awards, and 29 Flash Website Awards.

Now, let’s be honest here: Potential buyers of tires don’t give a hoot that BFGoodrich won an FWA award. There’s a 99.9% chance someone who is in the market for new tires has no idea what an FWA even is. But it’s extremely important for the marketing team at BFGoodrich.

Why?

Because at the next board meeting, someone from the marketing team is going to report that their new interactive website project won a bunch of awards.

The board members are going to sit back in their plush leather chairs, nodding their heads, and relishing in their company’s new awards. After all, this is recognition. Big time recognition for people in the marketing world.

And who are the heroes in this story?

The people in BFGoodrich’s marketing department that hired Grow.

And guess who’s going to make sure that’s remembered at the next salary / performance review meeting for the BFGoodrich marketing department?

You guessed it.

Grow might not typically pitch clients on the earning potential of their clients. The work they do is too fuzzy, and the scale too large, to really figure that out.

But I’ll bet they do a great job at showing their clients how they’re going to make them, the client, look like a superhero inside their department and their company.

How can you make your clients superheroes?

I often focus on money because it’s the currency we’re paid in. It’s easy to make the case that our clients should spend $1 to get $10 back. When return-on-investment is framed as direct money made as a result of a client project, it’s trivial to pitch hiring you as an investment.

Money in, money out.

But the hangup is often around pricing on value when the client doesn’t care about the actual, tangible, financial results of the project.

However, if you’re able to get to the root of what clients want — what status they seek as a result of working with you — you can make working with you the obvious choice.

In the case of a big corporation like BFGoodrich, everyone is probably pitching them on “give us your money and we’ll make you a flashy website.” Instead, pitch them on making their marketing department shine at their next company-wide meeting.

If you’re working with a non-profit, how can you help increase the prestige of their brand (and the indirect, additional donations and support they gain)?

And should you happen to find yourself pitching an early-stage startup, what’s that next step they’re looking for help with? Do they need help in raising their Series A round of funding? If so, what does that mean you can help them with? How will that affect the project you do for them?

When you know what your clients want — actual human beings who suffer from bouts of anxiety, fear uncertainty, and dream big — it’s better for you AND them to focus on what they actually want from you.

As a consultant, your focus should be to help your clients achieve greatness. To make them superheroes to themselves, their peers, and maybe even their bosses.

The work you actually end up doing for them is just an accidental by-product.

Selling to superheroes

The best advertisements never focus on the features of the product being promoted.

Apple initially sold FaceTime by reuniting people, and not just describing video conferencing from a smartphone.

In AMC’s Mad Men, Don Draper pitched Kodak on hiring his company by promoting their “Carousel” photo slide presenter as a time capsule of precious family memories, rather than a way to throw photos on a living room wall.

Great advertisements show the prospective buyer how their products will make their lives better.

And so, your project pitches need to show your clients how, through you, they’ll become badasses.

One of the best books I read over the last year was Kathy Sierra’s Badass. It’s a book about product design and development that’s best summed up with this excerpt from its overview:

The answers to what makes a sustainable bestseller aren’t in the successful product. The answers are in the successful product’s users. It’s not the product success that matters most, it’s the successful results of those who use it. Repeatedly. Consistently. Sustainably.

The answer to a sustainable bestseller is to shift the focus from making an awesome product to making an awesome user of that product. The answer lies is helping users become badass not just at using the product, but at whatever it is the product can help them do and be. And some of those answers are surprising, counterintuitive, but can be implemented by anyone at any stage in a product’s development. Even if you can’t improve your product, you can still improve your user’s experience by designing for what happens after they use it.

The easiest, most straightforward way to make your clients badass is to make them more money. And considering that we’re paid with money, being able to present yourself as a financial investment to your clients is a pretty sure way of making it clear that they can spend $X to make $Y, where $Y guarantees a better life and business.

But like we described above, not everything is reducible to dollars and cents.

So in these situations, we need to pitch clients the way the best Madison Avenue ad agencies design ad campaigns: by focusing on how our “product” — the work we do AND the effect it leaves on the client — will make our clients more badass.

Practical ways to make badass clients

In order to make your clients awesome, you first need to know what they’re looking for.

This means that asking them what kind of project they want, what it should look like, what it should do, and so on isn’t enough. That would be like Apple focusing on how FaceTime works, rather than why connecting people from opposite ends of the planet is so important.

If you’ve gone through my free course on raising your rates, you know that two things need to happen prior to issuing any proposal:

- Understand the why behind the project. What drove the client to wake up and reach out to somebody like you today? Why do they really need this project? Is their boss breathing down their neck? Are they looking to make their department rockstars in the minds of the board of directors?

- Understand the upside of the project. I primarily teach how to quantify the financial upside of a project (the probably return-on-investment), but in some cases we need to try to quantify what it would mean for your client — the actual human being who wants to work with you — to succeed through you.

When a project comes your way and you don’t have an easy way to quantify the value that you’re delivering to them, you’re going to need to shift your attention toward determining where are they right now and where do they want to be?